This site was created by a group of individuals who form the “Committee for Ben”.

None of its members are related to Ben Geen, nor are they from his circle of friends. They are merely individuals who believe that Ben is the victim of a gross miscarriage of justice and are campaigning for a fair trial. Those individuals include; Marty Hirst, Richard Gill, Wendy Hesketh & others.

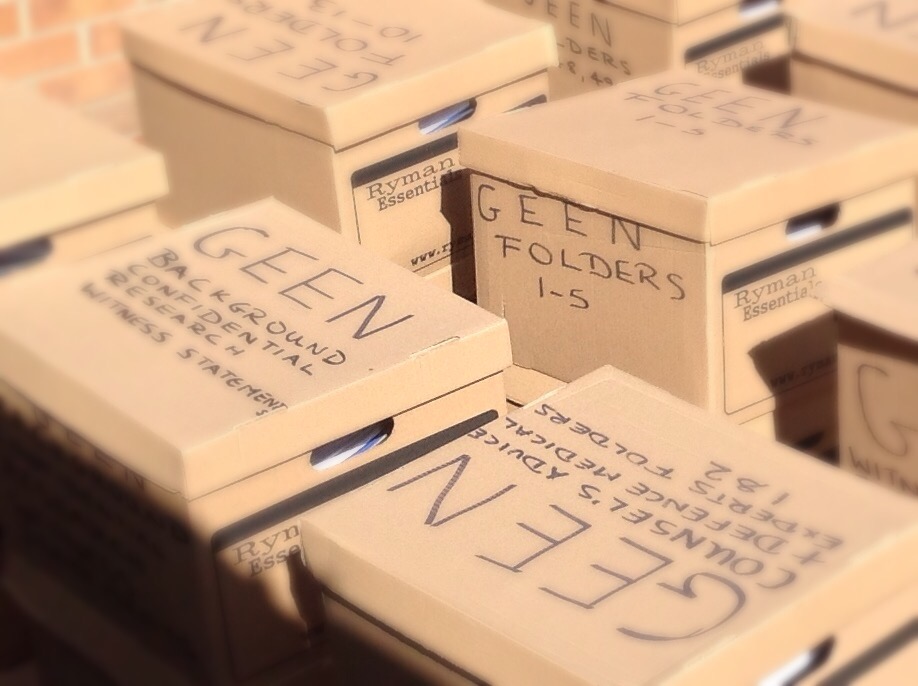

Original Documents

On this page can be found a number of links to various documents related to Ben Geen’s case.

Report of the Independent Review into the Horton General Hospital Accident & Emergency Department

Advice & grounds for appeal against conviction – 28 April 2008

Professor Jane Hutton’s report – Court of Appeal, 29 Sept 2009

Defence team’s grounds for appeal – Court of Appeal, 5th October 2009

Transcript of the court’s decision – Court of Appeal, 5th November 2009

Rarity of Respiratory Arrest in ED – Richard D. Gill, 9 July 2014

Statistics in the Dock (a summary of Ben’s situation)

Adapted from a piece written in 2010 by Nigel Hawkes on “Straight Statistics”

In April 2010 a court in Arnhem ruled that Holland’s worst-ever serial killer is innocent of the charges for which she was jailed for life in 2004.

Lucia de Berk, a paediatric nurse, was found guilty of seven murders and three attempted murders in a case that has close parallels with that of Sally Clark, the mother convicted in the UK of murdering her two children. In the Clark case, the expert witness Sir Roy Meadow declared that the chances of Mrs Clarks’ babies having both died as a result of cot deaths was 73 million to one against.

Her case also shares characteristics with that of Benjamin Geen, a British nurse jailed for 30 years in 2006 for murdering two patients and seriously harming 15 others. In Geen’s case, the court heard that he injected a series of patients with drugs that stopped their breathing in order to satisfy “a lust for excitement” when reviving them.

In both cases, the suspicions arose when hospital staff became convinced that the nurses were linked with a series of incidents too numerous to be coincidental. Investigations were launched but in neither case did they follow the scrupulous evidence-gathering needed to demonstrate a truly unusual pattern of events.

In the case of Lucia de Berk, the Dutch court was told by Dr Henk Elffers of the Netherlands Crime and Law Enforcement Research Centre that more children had died on her shifts than appeared possible by chance. He put the odds of her presence being a mere coincidence at one in 342 million, a staggering figure that seems to have blinded the court to any alternative explanation of the deaths.

There was little other evidence to convict her, except for traces of toxic substances found in two of the exhumed bodies. These were equivocal because they could have been caused by the treatments the children had had, and there was nothing to connect her directly to them. Lucia de Berk never admitted guilt, but was convicted in spite of there being no eye-witnesses and no direct incriminating evidence against her.

“Statistics drove the case from start to end” says the British-born statistician Richard Gill, Professor of Mathematical Statistics at the University of Leiden. “Statistics and psychology. Lucia’s conviction for serial murder, and even the ‘proof’ that there were any murders at all – let alone by whom – were almost entirely based on wrong statistical data, wrongly analysed, and wrongly interpreted, by amateurs.”

Professor Gill, who has lived in the Netherlands for 35 years, has been prominent in a campaign to have the case overturned. In dismissing her appeal in 2004, the judges explicitly wrote that statistics had not influenced their verdict, and that every one of the deaths had been indisputably proven to be unnatural. But when, thanks to the campaign, an expert was finally appointed to review the deaths he found that they could just as well have been natural.

The conduct of the case, in Professor Gill’s account, was extraordinary. Convinced she was guilty, the police and the managers of the Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague where she worked assembled a dossier in which every death became unnatural when it had occurred during, or after, a shift in which she had worked. For one of the alleged murders, it was established on appeal she had not even been in the hospital for three days around the time it occurred.

Taking account of the shifting numbers and using more appropriate statistical methods reduced the odds from 1 in 342 million to 1 in 48. A further analysis by Professor Gill further reduces the odds to one in nine. The odds, whatever they are, cannot prove guilt or innocence, but the contention of her supporters, who include the philosopher of science Ton Derkson and his sister, the doctor Metta de Noo, is that the original statistical claims led the police and the courts to conclude that any verdict other than guilty was unthinkable.

In Benjamin Geen’s case, papers are now before the Criminal Cases Review Commission casting doubt on the data used and its interpretation. At the request of his defence lawyers, Professor Jane Hutton of the Department of Statistics at Warwick University has prepared a report which says that the information presented in the case was “of inadequate quality”.

“The collection and analysis of data on cases of sudden collapse involving breathing difficulties (SCBD) is such that I do not think the evidence is of any value in assessing the frequency of patterns, hence it is not of value in making inferences as to causes. A statistical analysis, perhaps several, are required to evaluate unusual patterns” she writes.

She points out that there were five SCBD incidents at Horton General Hospital in December 2002, before Geen worked there, and six in December 2003, when he was working there. If all six of the 2003 incidents are linked to Geen, then the assumption must be that the rate of natural causes must be zero, whereas it is known to have been five in 2002. The probably of zero natural causes cases in 2003 is less than 1 per cent, she calculates, and the probability of one or fewer is 4 per cent.

Very similar calculations applied in the Lucia de Berk case. Initially she was linked to nine incidents in which children either died or required resuscitation, in a single year, and it was claimed that all had occurred during her shifts. But on closer examination it turned out that there had been 11 such incidents, seven on her shifts and four out of them. Seven of the incidents involved only three babies, so were not “independent” events as the court assumed.

What appears to have happened in both cases is described by Professor Hutton as “diagnostic suspicion bias”. Once suspicion was directed at the nurses, every unexpected event occurring while they were on duty tended to be attributed to them, without sufficient effort being made to discover alternative causes. The court in Geen’s case appears to have been given no numerical evidence of how rare SCBD is.

Lucia de Berk was released in 2008 when a retrial was ordered. She suffered a stroke while in prison, and is paralysed in one arm. The court in Arnhem subsequently concluded the case by declaring her innocent of the murders, a course of action urged on the court by the public prosecutors.

Ben Geen’s case has been taken up by the London Innocence Project, a non-profit legal resource clinic run from I Pump Court Chambers by barrister Mark McDonald and a team of law and journalism students. Geen’s appeal was rejected in November 2009, but the Criminal Cases Review Commission can send it back to the Appeal Court if it believes the conviction unsafe.

Nigel Hawkes

Ben’s Story

Based on an article in The Independent dated 28th February 2010 by Matthew Holehouse.

A NURSE jailed for 30 years for murdering two patients and seriously harming 15 others was convicted of crimes that never took place, new evidence suggests. Benjamin Geen, 29, was found guilty in 2006 of injecting patients with drugs that stopped their breathing in order to satisfy a “lust for excitement” when resuscitating them. Two men, David Onley, 75, and Anthony Bateman, 66, died. Appeal lawyers say Geen, a former Territorial Army lieutenant from Banbury, Oxfordshire, is the victim of a ‘witch-hunt’ in a health service determined to prevent a repeat of the case of Harold Shipman, the GP who murdered at least 200 of his patients. “There has been a major miscarriage of justice,” said Dr Michael Powers QC, Geen’s barrister. In February 2004, after a spate of respiratory arrests on the A&E ward, staff at Horton General Hospital became suspicious of Geen and called the police.

•(comment) there were five such recorded events in the same period of the preceding year and seven in this period, with very few recorded in between. This seasonal fluctuation is well-documented.•

Prosecutors told the jury at Oxford Crown Court that the pattern of 18 cases identified from patient records was so unusual it was the work of “a maniac on the loose” – and that only Geen was on duty in every case

•(comment) scores of identical cases were initially identified as “unusual” during the investigation only to be subsequently discarded as “no longer suspect” because there was no connection to Ben Geen. If these cases were indeed “the work of a maniac on the loose” then there must surely have been a second “maniac on the loose” to have caused all the “unusual and suspect” cases where Ben Geen was not on duty.•

Prosecution witnesses told the court that a variety of painkillers and sedatives administered by a rogue nurse were the most likely cause of such collapses.

•(comment) though no such evidence could be provided, for example in the form of toxicology reports.•

The jury agreed. Geen was acquitted of one charge, and sentenced to 17 life sentences. However, hundreds of pages of new evidence call into question the safety of that conviction. A new report by Prof Jane Hutton, a leading medical statistician, found that the Crown had no grounds to say that the ‘pattern’ of illness at the hospital was rare, or evidence of a murderer on the loose. “The evidence given… was of no value in supporting a conclusion that there was an unusual pattern, nor a conclusion that any unusual pattern was not a chance event,” she wrote. Opinions given by witnesses based on anecdotal evidence, such as that of a Horton A&E nurse in court who testified that respiratory collapses were very rare, were “very likely to be misleading.” “Most people do not keep accurate records of events, and memory is generally selective,” she wrote.

•(comment) statistical evidence subsequently compiled and interpreted by Prof.Richard Gill has proved that, though less common than cardio- or respiratory & cardio arrest (about five times less frequently recorded), respiratory arrest is a common enough occurrence in similar hospital departments for it not to suggest deliberate inducement by a third party.•

In the weeks following Geen’s arrest, the initial pool of ten victims under investigation by doctors at Horton grew to several dozen. How they and the police whittled those down to the 18 for whom charges were brought is not clear, and was not challenged in court. However, emails exchanged between senior doctors hunting for ‘victims’ following Geen’s arrest show they focussed on his patients, and that the task of examining casualty cards of 4,000 A&E patients who were not treated by Geen was given the lowest priority because they would take too long to examine. Defence lawyers say this proves that, from the start, the investigation was creating a pattern of cases that could lead only to one nurse.

•(comment) this is exactly what happened in the Lucia de B. case in the Netherlands – first identify your murderer and then look for some victims to attribute to her•

Geen’s case was rejected in November 2009 by the Court of Appeal. Judges refused to hear from new expert witnesses after ruling that their analysis did not amount to significant fresh evidence.

•(comment) they actually said that their evidence would amount to nothing more than common sense•

Lawyers then appealed to the Criminal Cases Review Commission. If it decides the evidence renders Mr Geen’s conviction unsafe, it can return it to the Court of Appeal.

•(comment) this is still ongoing. Four years later the CCRC has still not acted. We need to provide them with a “Novum” – new information or evidence – before they will proceed•

The jury found that seven patients collapsed after Geen injected them with muscle relaxants. This scenario is now questioned by a submission from Dr Mark Heath, a professor of clinical anaesthesiology at Columbia University, New York, and expert on lethal injections who has testified in US Supreme Court cases. On examining their records, he found the victims’ symptoms inconsistent with the paralysing effects of such drugs, which would leave the victim unable to breath but fully conscious. “There are many far more mundane causes of these events, and in none of the charts I reviewed does it appear to me that the administration of a muscle relaxant is a likely cause,” he wrote. “Conscious paralysis is subjectively an extraordinarily astounding and horrifying experience, it is difficult to imagine that any person… would fail to recall and relate that an extremely remarkable and awful event happened to them,” he wrote. Other new evidence suggests Geen did not kill David Onley. He had been admitted to A&E shortly after being discharged following triple heart bypass. He had a fever and a chest infection, and had two heart attacks in hospital. Doctors believed he was ‘on borrowed time’, but the jury decided Geen had administered drugs to stop his breathing, which triggered a fatal third heart attack.

However, a report after the trial by Dr Charles Pumphrey, b.8 July 1948 d.7 March 2012, commissioned in response to proceedings for damages made by Mr Onley’s family, found the cause of death was liver failure linked to septicaemia. Geen was never caught by CCTV or witnesses. Almost all the patients were elderly or seriously ill on arrival.

The clincher for court was the discovery of a syringe of muscle relaxant in Geen’s fleece pocket on the day he was arrested. Geen said he had taken it home by accident – a breach of nursing rules but, former nurses say, a common mistake. Police said it was a sign he was becoming more brazen and would kill again.

•(comment) Ben Geen’s explanation for the syringe in his fleece pocket was that it was inadvertently taken home after it having got there without him being aware – or remembering – during a hectic period in the Emergency room on his previous shift. His girlfriend had insisted (quite rightly) that he take it back into work for correct disposal. Though contrary to good nursing practice this hardly warrants a thirty year sentence. It has also been suggested that “a cocktail” of substances were “discovered” in and on that fleece jacket. The jacket was thoroughly tested and there were indeed trace elements detected of various chemicals and substances – including nicotine. These traces can be explained by Ben Geen often having worn that garment during clearing up after incidents.•

Only two patients were found to have traces of non-prescribed drugs in their urine. However, an internal hospital report into the incidents, written in September 2004 but not shown to the jury, found that record-keeping was flawed and that many casualty staff were failing to record drugs they legitimately administered. The report also calls into question the ‘unusual pattern’. In December 2003, when Geen was said to be beginning his spree of attacks, seven patients were taken from A&E into critical care after suffering respiratory arrest. But the previous December, the figure had been five, with very few in the intervening months. The report notes that such “an increase might be expected in the winter months” – but adds that nursing staff instead identified Geen as the cause. The fresh evidence came to light after Geen’s family wrote to London Innocence Project (LIP), an initiative for law students who investigate suspected miscarriages of justice. “We were shocked by how much of the conviction depended on evidence that should have been excluded due to its prejudicial bias,” said James Bromige, a trainee barrister at the time. LIP then launched a public campaign to support Geen’s appeal. The crown’s expert witness, Professor Alan Aitkenhead, who advised the police through the Geen investigation was an expert witness at the Shipman trial. Dr Powers said that doctors have become “suspicious” since Shipman – particularly of nurses. “There’s a climate that adverse events have got to be explained,” said Powers. “We’re very anxious to avoid disasters, and as soon as we get a whiff of one it’s very nice to tie it all up.” “It’s probably the heart of the risk of injustice: a desire to get a conviction. But there will be times when people are wrongly convicted.”

Central to a fresh appeal case is the judgement made in the appeal of Colin Norris, a Newcastle nurse found guilty of murdering four elderly patients with insulin injections. Judges upheld the conviction, but also ruled that in such cases an unusual pattern of illnesses was, on its own, worthless as evidence. Individual charges needed to be proven on their own merits. Lawyers believe that ruling, if applied to Geen’s conviction, would render it to be unsafe. “If the Court of Appeal had applied their approach in Norris to Ben’s case then he could have spent that Christmas with his family instead of in prison. It is of the utmost importance that our appeal is heard again at the first possible opportunity,” said Mark McDonald, a barrister and the founding director of LIP.

Nor, McDonald says, was the trial, which was held close to Horton Hospital, well handled. Jurors were found to have discussed the case with strangers, but were not discharged. The defence counsel was changed at a late stage, pushing the trial back four weeks and leading to repeated requests for adjournments. There was simply not enough time, defence lawyers say, to make sense of thousands of documents of complex medical evidence. Geen’s sister, Hayley, now 25, took up studies in 2010 to become a lawyer at Buckingham University in the hope of helping to free her brother. He has been held at Long Lartin high security prison since the summer of 2009, where he has been studying for an Open University degree and attending yoga classes. After moving from Woodhill prison, the governor at Long Lartin told Geen that he could no longer work as a Samaritan listener for other prisoners as his crimes were committed while in a position of trust. “It’s had such a big impact on all of us. You feel very guilty every day for getting on with your own lives,” said mother Erica, 51 a nurse. His father, Mick, 52, a newspaper printer from Milton Keynes, said at the time: “Ben always wanted to be a nurse. He is a caring person. He was in a TA medical unit, and if this miscarriage didn’t happen I’ve no doubt he would have been in Afghanistan. He wanted to serve in the Army and do his tour of duty. “We know, that he did not commit those crimes. That will never change,” he said. “The case was so theatrical and emotive, I thought it was some sort of American movie. You could tell, most of the evidence was going straight over the juror’s heads. I recall seeing some were asleep.

•(comment) trial by media was an obvious factor in this case. The press would note down every juicy detail that came from the prosecution council and, when it became time for the council for the defence to speak, quickly left the courtroom so as to file their stories with their editors.•

“We put our faith in the law all the way along. We sat through that court case believing that right would be done and Ben would walk out a free man. And it never happened.”

Statisticians back former nurse’s last chance to clear name

Leading statisticians have come out in support of a former nurse serving 30 years for murder in a final attempt to clear his name. The miscarriage of justice watchdog is expected to decide whether or not to refer the case of Ben Geen, currently in HMP Frankland, back to the Court of Appeal in the next few weeks. The Appeal judges have the power to overturn his conviction on two counts of murder as well as causing grievous bodily harm to 15 other patients.

Geen was portrayed in the press as ‘the nurse who killed for kicks’ and sent to prison in 2003. He was sentenced shortly after the publication of a report into the conduct of the GP Harold Shipman considered to be the UK’s most prolific serial killer. The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) had previously rejected the case but has been forced to reconsider their decision in the wake of a legal challenge.

• The Ben Geen case has featured on the Justice Gap here.

‘We have grave doubts as to the courts’ ability to get to grips with what was going on at the hospital,’ comments Professor Richard Gill, emeritus professor of mathematical statistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

At his three-month trial, the Crown’s lawyers argued that incidents of respiratory arrest were extremely rare and, unheard of, without cause. They claimed that ‘an unusual pattern’ had emerged at the A&E at Horton General, a small hospital in Banbury in Oxfordshire when 18 patients apparently suffered unexplained respiratory arrests in a three-month period.

A previously rejected application to the miscarriage of justice watchdog – backed by five leading statisticians including Sir David Spiegelhalter, of Cambridge University and Professor Norman Fenton, of Queen Mary’s University of London as well as Richard Gill – argued that the likelihood of a cluster of such events was far from unusual.

A soon to be published new paper – co-authored by Gill, Fenton as well as Professors David Lagnado from University College London and Martin Neil from Queen Mary’s – for the first time draws on data as to admissions at Horton General over a 13 year period with the critical three months when Geen was supposed to have been on a killing spree at its centre.

Prof Gill was involved in the successful campaign to overturn the conviction of the Dutch nurse Lucia de Berk – see below. According to the academic, up to mid-2004 admissions at the hospital were getting busier and busier. ‘The number of patients being treated in emergency almost doubled from 400 a month in 1999 to about 800 by the time of Ben’s arrest in February 2004,’ he explains. ‘Then the numbers collapse – no doubt, the fall was initially due to the public’s response to Ben’s arrest but it seems almost certain that the numbers fell (and stayed low for a long period) as deliberate policy of the local health providers. And nobody has ever said why they changed their policies.’

‘The claim that the emergency room was chronically understaffed during the critical months was part of Ben’s defence. It was denied by the hospital,’ Gill continues. He points out that Geen had complained about the situation times in the three critical months. ‘He was severely reprimanded by the chief nurse for doing so. The official line was everything was going fine,’ Gill says. ‘The reality was it was getting more and more chaotic and things were going wrong, patients were waiting too long. Everybody denied that.’

The new report argues that events might have been relabelled after hospital management suspected Geen. An internal investigation was launched after a 42-year-old diabetic alcoholic arrived on a Thursday afternoon complaining of abdominal pains. Within hours he was fighting for breath, put on a life support machine and later died. It was the second time that day that a patient appeared to suffer an unexpected respiratory arrest.

Senior staff at Horton General called in doctors from nearby John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford and, over the weekend, went through case notes. Ben Geen was the only member of staff under suspicion. By the end of the weekend, the team identified 18 patients as having suffered an unexplained respiratory arrest and on each occasion Geen had been on duty. ‘They did not look for events outside his shifts,’ says Gill. ‘Many of the events they identified had not even been thought of as in any way suspicious before. Some were very mild and did not lead to admission to critical care. Many other of those patients were on their way to critical care anyway.’

The following Monday, Ben Geen was arrested. As he arrived for a night shift, he was called into a meeting. He had a syringe in his jacket pocket and discharged its contents into its lining. The prosecution alleged that the man whose death sparked the investigation tested for two of the drugs (vecuronium and midazolam) in the syringe.

According to the new paper, the classification of such collapses is far from precise at the best of times and certainly not in an understaffed environment. A diagnosis of ‘cardio-respiratory’ arrest, where the heart stops working and consequently the lungs fail, is far more common than pure ’respiratory arrest’ where the lungs stop working, and hypoglycaemic episodes, involving a fall in blood glucose level causing fainting.

The new report argues that the data over the 13 year period for the total number of arrests over the critical three month period was completely in line with what would be expected. However what was striking about the period leading up to Geen’s arrest was the unusual mix and, in particular, the high proportion of cases identified as ‘respiratory arrest’. ‘Normally, there are five times as many cardio-respiratory arrests as respiratory arrests. Now it was the other way round,’ explains Gill. ‘Why does the number of cardio-respiratory arrests fall so suddenly in those three months? Do we really believe that there were no cardio-respiratory arrests in December 2004?’

According to Gill, it was ‘pretty clear’ that there was ‘a massive re-classification on those few days after the two cases that were the trigger for Ben’s arrest’. He continues: ‘When one looks at the medical data on those 18 patients it is clear that labelling of events is very, very arbitrary. Some ‘arrests’ were so brief that they probably should not have been called an “arrest” at all.’

Prof Norman Fenton says that ‘from a purely probabilistic viewpoint, there was always a problem with the assumption that such a cluster of “incidents” happening in a short time period with the same nurse on duty each time could not have happened by chance’. He continues: ‘Even if we ignore the possibility – as suggested by the new evidence – that at least some of the incidents may have been misclassified, the probability of such a cluster happening is not especially low. When we look at the newly available admission data for the extended period, the idea that the ‘cluster’ can only have been caused by malicious intervention is even more dubious.’

Lucia de Berk: Statistics drove the case from start to end

The following is an extract from Guilty Until Proven Innocent (Biteback 2018) by Jon Robins

Lucia de Berk, a paediatric nurse, was found guilty of seven murders and three attempted murders of children in her care at Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague in 2003. She was reckoned to be the Netherlands’ most prolific serial killer. At least she was until she was exonerated in 2010. Now her case is recognised as one of the country’s gravest miscarriages of justice.

The court heard that more children died on her shifts than could possibly be explained away by coincidence. The odds of her having been present by chance was reckoned to be one in 342 million. The alleged murders and attempted murders were claimed to have taken place at three hospitals between 1997 and 2001. They came to light after police began investigating the death of a baby girl named Amber. Her conviction was based on two deaths, including that of Amber, which toxicology reports suggested could have been a result of poisoning.

Statistics drove the case from start to end, according to British-born statistician Richard Gill, emeritus professor of mathematical statistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. Gill campaigned for de Berk’s conviction to be overturned. ‘Why do we know beyond reasonable doubt that Lucia is innocent? Because an independent multidisciplinary scientific team of medical specialists, toxicologists were finally allowed complete access to complete medical dossiers of key cases,’ Gill told me. ‘They discovered that the alleged incident in each of those cases was entirely natural – though in each case there was a heap of medical errors and all kinds of important information had earlier been withheld from the courts.’

Just like the de Berk case, Geen’s began with the hospital handing over the murderer to the police. Typically, murder investigations begin with ‘an evidently murdered person’ (Dr Gill’s words) and the police are called in to find the perpetrator. However, in these cases that principle has been inverted; the police go with the story as told by the medics. ‘As we know, “medical collegiality” means that that story will be very consistent,’ he said. ‘No one will break ranks and tell a different story.’

Prof Gill argued that the fact of Geen’s presence came to be what defined an incident as an ‘incident’. Again, that is what happened in the de Berk case. The two cases highlight the difference between the British adversarial legal system and the Continental inquisitorial system. In the Netherlands, the court can appoint a scientist to lead an investigation, which means that the judge and jury do not have to depend on the expert witnesses called by the prosecution and defence.

In Prof Gill’s view, Ben Geen was convicted simply because the prosecution had the more persuasive experts. ‘Unfortunately, Ben will never get a fair trial until medical experts start speaking out on his behalf. I am afraid that their ranks are closed,’ he said. ‘Lucia got a fair retrial because there was a medical whistleblower, well placed in society and with inside knowledge who fought for seven years.’

Jon is editor of the Justice Gap. He is a freelance journalist. Jon’s books include Guilty Until Proven Innocent (Biteback, 2018), The First Miscarriage of Justice (Waterside Press, 2014), The Justice Gap (LAG, 2009) and People Power (Daily Telegraph/LawPack, 2008). Jon is a journalism lecturer at Winchester University and was a visiting senior fellow in access to justice at the University of Lincoln. He is twice winner of the Bar Council’s journalism award and won Halsbury Legal’s journalism award

“Making a Murderer”

In the 3rd of a new series of new articles examining the failings of our criminal justice system, Jon Robins Times Writer and Editor of the Justice Gap highlights the the injustice of Ben’s wrongful conviction and miscarriage of Justice.

Reminding us that we should all be worried because one day “This Could happen to You”

The deeply flawed case against Ben Geen, based on flawed statistics misunderstood by prosecution, a jury blinded by science, firmly endorsed by a remarkably stubborn Court of Appeal. The UKs version of “Making a Murderer”

https://bylinetimes.com/2019/03/13/the-justice-trap-murder-by-numbers/

CCRC agrees to reassess Ben’s case!

Rather than contest in court the CCRC have today agreed to take Ben’s case back and to reassess our application with a new case worker and commissioner.

There is an ever growing swell of support for Ben’s case and momentum is growing day by day.

This article by Jon Robins, editor of The Justice Gap, explains all;

ABC Radio Report: “An Unusual Pattern”

Norman Swan, from the Australian Broadcasting Company’s “Health Report” program, has aired a report on Ben’s situation.

Click HERE to listen to the report

Judicial Review of the CCRC’s decision!

Ben’s legal team have today been granted permission by the high courts to challenge the CCRC’s decision not to review the conviction based on new statistical evidence. It is vary rare and almost unheard of. The Justice gap website has just published a piece on this development.

Lawyers are challenging a decision by the miscarriage of justice watchdog not to refer the case back to the Court of Appeal in a final attempt to have his conviction overturned.

Last October the Criminal Cases Review Commission decided not pursue the case of Ben Geen, who is serving time for crimes that were never committed.

‘We have to judicially review the decision. It is the only step that we have left to take,’ Ben’s father Mick Geen tells the Justice Gap. ‘We have been with the commission for two years and it has come to nothing. We have very good new evidence, probably the most compelling that we have had in the last nine years.’

The Justice Gap article in full, by John Robins

Article By Hannah Devlin- The Guardian 15/02/2015

Statisticians question evidence used to convict nurse of murdering patients

Experts concerned that ‘extreme rarity’ of respiratory arrests, claimed by witnesses at 2006 trial of Ben Geen, was made without required analysis.

By Hannah Devlin

Four eminent statisticians have raised concerns about the quality of evidence used to convict a nurse of murdering two patients and poisoning 15 others.

Ben Geen, 34, is serving a 30-year sentence after being convicted in 2006 of injecting patients with a variety of drugs in order to “satisfy his lust for excitement” when reviving them. There were no witnesses to the crimes, but Horton General hospital in Banbury identified an “unusual pattern” of respiratory arrests, which the prosecution said could only be explained by a member of staff deliberately harming patients.

Now Sir David Spiegelhalter, of the University of Cambridge, has voiced concerns that the “extreme rarity” of respiratory arrests, claimed by expert witnesses at trial, was made without the methodical evidence-gathering and detailed analysis required.

“I have no opinion on the innocence or guilt of Ben Geen, but I do feel that the statistical evidence in this case was not handled properly,” he said.

Geen’s legal team has submitted independent reports by Spiegelhalter, Prof Norman Fenton, Prof Stephen Senn and Prof Sheila Bird to the Criminal Cases Review Commission in a bid to have the case referred to the appeal court, which has already upheld the conviction once.

Geen, a former Territorial Army lieutenant, was arrested after a cluster of incidents during the winter of 2003-4 in which patients stopped breathing or collapsed without warning. The court was told that the sequence of events – including the deaths of two patients, Anthony Bateman, 66, and David Onley, 75, who were already gravely ill – was so exceptional it could only be explained by “a maniac on the loose” at Horton General hospital.

Geen was pinpointed as a suspect because he had treated all of the patients and when arrested he had a syringe containing a muscle relaxant drug in the pocket of his fleece.

The defence contends that the deaths and respiratory arrests can be explained by natural causes and that Geen was the victim of a “witch-hunt” by hospital management. Geen says he took the syringe home accidentally following a busy A&E shift.

Geen’s defence has drawn parallels with the case of Sally Clarke, in which flawed statistics were used to secure a murder conviction that was subsequently overturned.

“My submission to the CCRC says that assessing whether events are unusual or surprising should not be left to intuition,” said Spiegelhalter. “I don’t trust my own intuition when an apparent coincidence occurs; I have to sit down and do the calculations to check whether it’s the kind of thing I might expect to occur at some time and place.”

In his analysis, Fenton, of Queen Mary University of London, concludes that, though 18 respiratory arrests in a two-month period is high, at least one hospital in the country would be expected to see this many events over a four-year period, purely by chance. “It didn’t seem a particularly unusual sequence of events,” he said. “If that was the starting point for the inquiry then that’s problematic.”

Senn, a medical statistician at the Luxemburg Institute of Health, said the evidence-gathering appears to have been potentially biased. “It’s almost as though the evidence was being collected to convict Ben Geen rather than being collected to assess the chances of guilt,” he said.

Previously the CCRC has ruled that besides the statistics, “a cogent and compelling body of evidence” indicated Geen’s guilt – in particular the syringe in his pocket and the rapid decline of some patients after coming under his care.

The CCRC is reviewing the case of a second nurse – Colin Norris – convicted of murdering four elderly women who had each suffered from low blood sugar levels. Again there were no witnesses, but the nurse was identified as a “common factor” in the deaths.

A spokesman for the commission said: “We have received extensive further submissions in response to our provisional decision not to refer Mr Geen’s convictions to the court of appeal. We will be carefully considering all those submissions before making any final decision in the case.”

Richard Thorburn, whose father John fell into a coma for six days after being treated by Geen, told The Times in December he believed the nurse had been rightfully convicted. “My father spent five or six days in a coma and although he survived he never fully recovered and died in 2009,” said Thorburn.

Spiegelhalter argues the case is illustrative of wider problems with how courts handle statistics. “They like either incontrovertible numerical facts, or overall expert opinions. But statisticians deal with a delicate combination of data and judgment that gives rise to rough numbers, and these don’t seem to fit well with the legal process.”

Making a lottery out of the law

An article by Tim Harford in the UNDERCOVER ECONOMIST 30 Jan 2015

‘The cure for “bad statistics” isn’t “no statistics” — it’s using statistical tools properly’

The chances of winning the UK’s National Lottery are absurdly low — almost 14 million to one against. When you next read that somebody has won the jackpot, should you conclude that he tampered with the draw? Surely not. Yet this line of obviously fallacious reasoning has led to so many shaky convictions that it has acquired a forensic nickname: “the prosecutor’s fallacy”.

Consider the awful case of Sally Clark. After her two sons each died in infancy, she was accused of their murder. The jury was told by an expert witness that the chance of both children in the same family dying of natural causes was 73 million to one against. That number may have weighed heavily on the jury when it convicted Clark in 1999.

As the Royal Statistical Society pointed out after the conviction, a tragic coincidence may well be far more likely than that. The figure of 73 million to one assumes that cot deaths are independent events. Since siblings share genes, and bedrooms too, it is quite possible that both children may be at risk of death for the same (unknown) reason.

A second issue is that probabilities may be sliced up in all sorts of ways. Clark’s sons were said to be at lower risk of cot death because she was a middle-class non-smoker; this factor went into the 73-million-to-one calculation. But they were at higher risk because they were male, and this factor was omitted. Which factors should be included and which should be left out?

The most fundamental error would be to conclude that if the chance of two cot deaths in one household is 73 million to one against, then the probability of Clark’s innocence was also 73 million to one against. The same reasoning could jail every National Lottery winner for fraud.

Lottery wins are rare but they happen, because lots of people play the lottery. Lots of people have babies too, which means that unusual, awful things will sometimes happen to those babies. The court’s job is to weigh up the competing explanations, rather than musing in isolation that one explanation is unlikely. Clark served three years for murder before eventually being acquitted on appeal; she drank herself to death at the age of 42.

Given this dreadful case, one might hope that the legal system would school itself on solid statistical reasoning. Not all judges seem to agree: in 2010, the UK Court of Appeal ruled against the use of Bayes’ Theorem as a tool for evaluating how to put together a collage of evidence.

As an example of Bayes’ Theorem, consider a local man who is stopped at random because he is wearing a distinctive hat beloved of the neighbourhood gang of drug dealers. Ninety-eight per cent of the gang wear the hat but only 5 per cent of the local population do. Only one in 1,000 locals is in the gang. Given only this information, how likely is the man to be a member of the gang? The answer is about 2 per cent. If you randomly stop 1,000 people, you would (on average) stop one gang member and 50 hat-wearing innocents.

We should ask some searching questions about the numbers in my example. Who says that 5 per cent of the local population wear the special hat? What does it really mean to say that the man was stopped “at random”, and do we believe that? The Court of Appeal may have felt it was spurious to put numbers on inherently imprecise judgments; numbers can be deceptive, after all. But the cure for “bad statistics” isn’t “no statistics” — it’s using statistical tools properly.

Professor Colin Aitken, the Royal Statistical Society’s lead man on statistics and the law, comments that Bayes’ Theorem “is just a statement of logic. It’s irrefutable.” It makes as much sense to forbid it as it does to forbid arithmetic.

These statistical missteps aren’t a uniquely British problem. Lucia de Berk, a paediatric nurse, was thought to be the most prolific serial killer in the history of the Netherlands after a cluster of deaths occurred while she was on duty. The court was told that the chance this was a coincidence was 342 million to one against. That’s wrong: statistically, there seems to be nothing conclusive at all about this cluster. (The death toll at the unit in question was actually higher before de Berk started working there.)

De Berk was eventually cleared on appeal after six years behind bars; Richard Gill, a British statistician based in the Netherlands, took a prominent role in the campaign for her release. Professor Gill has now turned his attention to the case of Ben Geen, a British nurse currently serving a 30-year sentence for murdering patients in Banbury, Oxfordshire. In his view, Geen’s case is a “carbon copy” of the de Berk one.

Of course, it is the controversial cases that grab everyone’s attention, so it is difficult to know whether statistical blunders in the courtroom are commonplace or rare, and whether they are decisive or merely part of the cut and thrust of legal argument. But I have some confidence in the following statement: a little bit of statistical education for the legal profession would go a long way.

Article in the Times 15th Dec. 2014

Nurse ‘was victim of Shipman hysteria’ Ben Geen is serving a 30-year sentence for murdering two patients.

Ben Geen is serving a 30-year sentence for murdering two patients.

Hannah Devlin, Science Editor and Sean O’Neill, Crime Editor

Published in The Times newspaper on December 15 2014

Hospital patients said to have been killed or poisoned by a “thrill-seeking” nurse may have died or collapsed as a result of natural causes, fresh evidence suggests.

Independent statistical research has emerged that raises doubts about the jailing of Ben Geen, who is serving 30 years for the murder of two patients and the grievous harm of 15 others, but the research cannot be heard in court.

Geen, 34, an ex-army reservist, was convicted in 2006 of injecting patients with potentially lethal drugs causing them to stop breathing so that he could “satisfy his lust for excitement” by reviving them. However, his legal team has argued that the respiratory arrests suffered by patients were not the “extremely rare” events portrayed at his trial.

Mark McDonald, a barrister, said Geen was imprisoned for “crimes that were never committed but created to fit the circumstances”. He said the authorities had been looking for a scapegoat because of fears over a serial killer in the hospital.

Geen’s lawyers approached statisticians because of concerns that the prosecution’s claims of the rarity of the incidents were made without the careful evidence-gathering needed to show a truly unusual pattern of events. They said the case raised the same questions about expert evidence as the case of Sally Clark, wrongly convicted of murdering her two baby sons in 1999 partly on the basis of flawed statistics.

A last-ditch attempt is now being made by Geen and his campaigners to persuade the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) to refer the case to the Appeal Court, which has already upheld the conviction once.

Geen was arrested after a series of incidents over two months in 2003-2004 at the emergency department of Horton General Hospital in Banbury, Oxfordshire, when patients suddenly stopped breathing or collapsed. Oxford crown court was told that the pattern of collapses, which included the deaths of two patients who were already seriously ill, Anthony Bateman, 66, and David Onley, 75, was so unusual that it had to be caused by “a maniac on the loose”.

There were no witnesses, but the hospital identified Geen as the prime suspect because he had treated all the patients. When arrested by police, he was found with a syringe containing a muscle relaxant drug. However, statisticians said that the claim that respiratory arrests in A&E were rare and the incidents at Horton had to be suspicious was a subjective impression and not a reliable scientific finding.

Jane Hutton, of the University of Warwick, said evidence given at the original trial “was of no value in supporting a conclusion there was an unusual pattern, nor a conclusion that any unusual pattern was not a chance event”.

The key issue was the poor quality of the evidence relied on by the courts, she said, adding: “I’m not taking a stance on innocence or guilt. There are standards of evidence and these weren’t met.”

After gathering data from similar-sized hospitals, Richard Gill, of the University of Leiden, in the Netherlands, said respiratory arrests in A&E departments were not rare. He said Horton hospital’s own records showed another cluster of five such incidents in December 2002, before Geen worked there.

At Geen’s first appeal in 2009 three judges declined to hear expert statistical evidence, saying they were satisfied with medical professionals’ view that a spate of respiratory arrests was rare. The CCRC said it did not want to refer the case to the Appeal Court again, and has questioned the quality of the new research, claiming the data it is based on is inadequate. However, Geen’s supporters said that the data was incomplete because hospital record-keeping was poor, which raises further concerns about his conviction.

The commission said that there was “a cogent and compelling body of evidence” pointing to Geen’s guilt — notably the syringe in his pocket and the sudden decline of some patients after contact with him.

Dr Malcolm Benson, an ex-medical director at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford who reviewed 5,000 sets of patient notes to help to identify victims, said it was the “unexplained nature of the [respiratory] arrests rather than the number” that convinced him that crimes had taken place. Geen had been the nurse in all the suspicious incidents.

From Long Lartin prison, where he has been awarded a law degree, Geen protested his innocence. He said he was present when patients were being revived because he was a military-trained medic capable of helping in emergencies. His explanation for the syringe was that he often went home after a long shift in his scrubs and NHS fleece. Geen said: “I was full of confidence and enthusiasm, I would always put myself forward to work in demanding situations but because I was newly qualified staff probably felt threatened by me.”

Geen, who volunteers as a “listener” to help prisoners who may feel suicidal, said: “I need to keep busy whilst in prison, because I know that it will be many years before I can prove my innocence.”

Richard Thorburn, whose father John lost consciousness after being treated by Geen, said he believed the nurse was properly convicted. “My father spent five or six days in a coma and although he survived he never fully recovered and died in 2009,” said Mr Thorburn. “Geen was a major contributory factor to my father’s pain and poor health over his remaining years.”

Nurses in the dock

Lucia de Berk The Dutch nurse was convicted of seven murders and three attempted murders in 2000 and 2001 but had her convictions quashed in 2010. Professor Richard Gill, who believes Ben Geen is a victim of a miscarriage of justice, helped to expose errors in the statistical evidence against her.

Colin Norris The Scottish nurse is serving life for murdering four patients at a Leeds hospital by insulin poisoning 13 years ago. Doubts about his convictions will be highlighted tonight by Panorama on BBC One.

Rebecca Leighton The Stockport nurse won damages from Greater Manchester police this year after being wrongly accused of poisoning patients and held in custody for six weeks.

Jani Adams She was labelled the “death angel” after being accused of murdering a patient at a Las Vegas hospital in 1980. However, the case against her collapsed when records showed that the patient was seriously ill and died of natural causes.

Jessie McTavish A nursing sister in Glasgow, she was jailed for murdering an elderly patient with an insulin injection in October 1974. However, her conviction was quashed five months later.

Original Times Newspaper article

HERE

Doing good statistics

The organisation “Inside Justice” – has shown interest in Ben’s case and has published an essay by Statistician Richard Gill, text here below.

The original can be found on the INSIDE JUSTICE website.

“Imagine if you asked people to roll eight dice to see if they can ‘hit the jackpot’ by rolling 8 out of 8 sixes. The chances are less than 1 in 1.5 million. So if you saw somebody in the UK – let’s call him Fred – who has a history of ‘trouble with authority’ getting a jackpot then you might be convinced that Fred is somehow cheating or the dice are loaded. It would be easy to make a convincing case against Fred just on the basis of the unlikeliness of him getting the jackpot by chance and his problematic history.

“But now imagine Fred was just one of the 60 million people in the UK who all had a go at rolling the dice. It would actually be extremely unlikely if less than 25 of them hit the jackpot with fair dice (and without cheating) – the expected number is about 35. In any set of 25 people it is also extremely unlikely that there will not be at least one person who has a history of ‘trouble with authority’. In fact you are likely to find something worse in the UK, since about 10 million people there have criminal convictions, meaning that in a random set of 25 people there are likely to be about 5 with some criminal conviction. And plenty of others will have other dark events in their life histories.

“So the fact that you find a character like Fred rolling 8 out of 8 sixes purely by chance is actually almost inevitable. There is nothing to see here and nothing to investigate. Many events which people think of as ‘almost impossibe’/’unbelievable’ are in fact routine and inevitable: see for instance this article on “Impossible Events” or Norman Fenton and Martin Neil’s book “Risk assessment and decision analysis with Bayesian networks ” section 4.6.3 “When Incredible Events Are Really Mundane”, or the book “The Improbability Principle” by David Hand (past president of the Royal Statistical Society).

“Now, instead of thinking about ‘clusters’ of sixes rolled from dice, think about clusters of patient deaths in hospitals. Just as Fred got his cluster of sixes, if you look hard enough it is inevitable you will find some nurses associated with abnormally high numbers of patient deaths. In Holland a nurse called Lucia de Berk was wrongly convicted of multiple murders as a result of initially reading too much into such statistics (and then getting the relevant probability calculations wrong also). There have been other similar cases. In the UK it seems that Ben Geen may also have been the victim of such misunderstandings.”

The dice throw analogy is very accurate, when we look at “health care serial killers”. A typical full time nurse works roughly half of the days of the whole year (take account of holidays, training courses, absence due to illness, “weekends”), and then just one of the three hospital shifts on a day on which she works. That makes 1 in 6 shifts. So if something odd happens, there is 1 in 6 chance it happens on his/her shifts. (However … more incidents happen in weekends and some nurses have more than average weekend shifts). But there is the question: which shift did some event actually happen in? There’s a lot of leeway in attributing some developing medical crisis situation to one particular shift. Then there is the question, which shift did the nurse have? There is overlap between shifts, and anyway, sometimes a nurse arrives earlier or leaves later. This gives hospital authorities a great deal of flexibility in compiling statistics of shifts with incidents, and shifts with a suspicious nurse. Both in the Ben Geen and in the Lucia de Berk case, a great deal of use was made of this “flexibility” in order to inflate what seems to have been chance fluctuations into such powerful numbers that a statistical analysis becomes superfluous: anyone can see “this can’t be chance”. Indeed. It was not chance. The statistics were retrospectively fabricated using a prior conviction on the part of investigators (medical doctors at the same hospital, not police investigators) that they have found a serial killer. After that, no-one doubts them.

What happened in both Lucia and Ben’s case is therefore not only the surprising coincidence but the magnification of a coincidence after it has been observed. Doctors look back at past cases and start reclassifying them. So the dice analogy is not quite correct: it is more like you see someone rolling 5 out of 8 sixes (and it’s someone you think is a bit odd in some way), and then you turn over the three non-sixes and make them into sixes too. Then you go to the police: “8 out of 8”. This is exactly Lucia: 9 out of 9 – but actually three or four of those dice outcomes had been altered. It’s just the same for Ben Geen. He was even convicted of causing the respiratory arrest of a patient who was admitted to the emergency ward on which Ben worked … after all there were so many of those events and always it seemed when he was on duty … yet it turns out that that particular arrest had already occured in the ambulance on the way to the hospital! It seems nobody checked.

Returning to the 8 dice throw analogy, a further twist to the story is that you never took the trouble to look at a further 20 dice-throws which had also been done and in which, surprise surprise, there are only two or three sixes. The eight dice throws which came to your attention are ones which you remember. Back to the hospital, you remember those 8 events precisely because that striking nurse about whom people have been gossiping was there. Neither in the Lucia case, nor in the Ben Geen case, did anyone take the trouble to go through all the shifts when Lucia or Ben had not been present, investigating the records to see if incidents had actually happened there too: incidents which should have gone into the statistics.

Doing good statistics might be not much more than common sense, it might not be rocket-science … but it is something which is incredibly easy to get very very wrong, with devastating effects.